My son Harry and I had weaseled our way into the cloistered beauty of

Oxford’s Magdalen College on May Morning, a few hours after gathering with

20,000 other revelers to greet the sunrise with a hymn sung from the medieval

tower, a tradition dating back 500 years. The college had sponsored a jolly day

of artistic expression and laid out a banquet of tools for our use: oil

pastels, Staedtler pencils, Winsor and Newton watercolour sets.

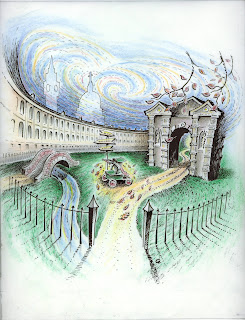

We sat on the striped lawn and sketched the arcaded front of the New

Building (c.1733), adding to the plump sketch books we carried everywhere on

this father and son tour of England. Increasingly, our pens and black books

were our go-to recording devices, cameras staying more often in the backpacks.

A window on the second floor had once been C.S. Lewis’s room. I made a

point of detailing the graceful Georgian sash. “You should flog your sketches

to the college,” suggested one observer. But we didn’t: it wasn’t about that.

It was about imprinting the day on our minds and hearts, capturing the moment

with a physical act. Even now, five years later, I can flip open to those pages

and smell the clematis that wound around the solid columns, hear laughter and

the crack of a croquet ball on the lawn behind us, see the radius of the Palladian

arches, feel the warmth of the May morning sun as it fluttered through the

dappled leaves of Oxford. One look at the sketch and it all comes back to life.

Sketching allows all this. Drawing is to photography what walking is to

driving: it’s more work, it’s slower, it demands patience and it’s something

we’ve increasingly forgotten how to do. And yet, it pays dividends: The work is

a rewarding pleasure, the pace allows a scene to sink in and be appreciated,

concentration breeds a patient contemplative mind-set … and it’s something that

can be relearned.

And it’s not all about great art, or skill. Drawing is something

everyone can do. I don’t use an eraser or straight edge when I sketch:

misplaced lines, side doodles, quirky shapes are all part of it.

A Princeton study in 2014 demonstrated the advantages of taking notes

long-hand, versus typing them into a laptop: more self-editing and more

emphasis on certain words rather than just a verbatim recording. With

sketching, these same things seem to hold true, and there is more. To sketch a

scene is to truly observe it. As Sherlock said to Dr.Watson: “You see but you

do not observe. The distinction is clear.”

That, and the physicality of putting pen to paper. There is a visceral

muscle-and-nerve connection to the scene in front of you when your mind

observes a shape and tells your hand how to bring it to a blank page. There’s a

pleasure in it that gives the intellectual imprint depth and substance. The

wide net of digital point-and-shoot is fine for a quick pass, but it’s largely

a glancing surface treatment and the real work is left to the camera. To sketch

a scene challenges our notions of what really matters as we move through a new

city or react to the beauty of a great, windswept plain.

It’s heartening to see that sketching is gaining the respect it

deserves. At the Rijksmuseum, an important arts and history museum in the heart

of Amsterdam, visitors are encouraged to put down their selfie-sticks and

cameras and use a sketchbook when they visit the museum’s displays, making

small drawings of sculptures and paintings rather than snapping a photo and

moving along quickly. “In our busy lives we don’t always realize how beautiful

something can be,” Wim Pijbes, the general director of the Rijksmuseum, told

the art blog Colossal. “We forget how to look really closely. Drawing helps

because you see more when you draw.” The story ran with photos from this

experiment showing wide-eyed children gazing at display cases with determined

intensity, pencils poised above sketchpads, fully engaged.

To our three kids, travelling with a sketchbook is not a new concept:

in cafés, museums, parks, sitting on a bus or on the brink of a gorge. Not only

do they seem to gain a bigger appreciation of beauty, they see detail and

nuance, entering into the experience of the place. They’ve been able to be

truly in the moment, rather than living in some strange parallel world of

constant screen time.

If this sounds like a Luddite fantasy, then yes, that’s part of it: a

yearning for a pared-down mode of travel, a rejection of the superficial and

instant. Sketching is, by nature, an old-fashioned way of seeing. Kids seem to

understand instinctively.

If this sounds like a Luddite fantasy, then yes, that’s part of it: a

yearning for a pared-down mode of travel, a rejection of the superficial and

instant. Sketching is, by nature, an old-fashioned way of seeing. Kids seem to

understand instinctively.

Recently, in Rome, I set myself a challenge: no cappuccino without at

least a full page in the sketchbook. I haunted the streets of Trastevere and

made a painfully slow progression through the ancient Forum, taking increasing

pleasure in the small moments afforded by sketching little pieces of antiquity,

Ducati motorcycles and crowded markets. On Via Merluna I sat at a red café

table, the foamy cappuccino disappearing from my glass at the same pace that a

sketch of the street scene appeared on my page. The scene was actually pretty

banal; just another street. But as I sketched, it became so much more.

A little crowd, including my excited waiter, gathered around, judging

my vision against what they saw and curious about my approach. They wouldn’t

have stopped for a selfie-stick. I had enough Italian to know that they

approved.