Published in Facts and Arguments, an anthology edited by Moira Dann, published by Penguin Canada, 2002

There had been altogether too much talk about crisis and security and air strikes and danger. We had just returned from a fall visit to England and even four-year-old Sam, innocence personified, had been part of a world that left no one untouched. No dream unmolested, not even his.

“I dreamed about plane crashes in my last sleep,” he told me.

The world was too much with us. It was time to get the boots on and head for The Back Field.

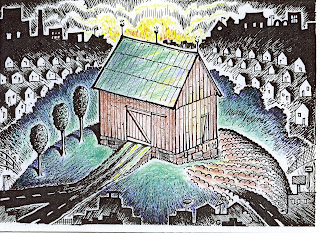

A world apart, The Back Field rises from the windy northern quarter of our farm, cresting like a slow rolling wave over the ice-age hill, full and complete in its encircling palisade of oak, maple, white birch and spruce. Early on a good crisp day in October, if I’m lucky, the geese will just skim the hilltop and I can feel and hear the wind vortices of their V-formation just above me as they head south. Maybe a fox will pass; last spring there was a bear.

But today there would be no geese. Just Sam and I, surrounded by the ancient trees and saplings, wind-tossed cloud cover and distant rumblings of winter.

Katy and I had always wanted to give shelter to the childhood realms of our kids. If it was possible to build a storybook world and let them live in it, then good. If free from the tarnishing influence of the 21st century’s darker aspects, then better. And this field, at the centre of our old farm, hours away from the city, worlds away from the war zones, was where we directed the little hands and feet for the most quiet peace of all.

So Sam and I walked and talked. He could talk a lot, as four-year-olds often can, and, freed from the dumbfounding sensory overload of Piccadilly Circus and Trafalgar Square, he was able to air out his mind and go off on a rich variety of tangents: Bob the builder. When’s my birthday? I am Robin Hood, watch me shoot my bow and arrow. What am I getting for Christmas? Daddy, are you a hero?

I didn’t much like that last one. To him, I hoped I was a hero, but he was getting around to something deeper and more troublesome. He’d heard the television news in passing, seen the coloured photos in The Times, heard discussions on the Underground, seen the soldiers at the fenced-off entry to Downing Street.

A walk in The Back Field had to be an antidote, however gradual. Farmer Ron Hewitt had ploughed while we were away and the soil smelled rich and full of promise. Next August, this field would be a sea of his special strain of sweet corn.

“Raccoons love corn, Sam. Let’s talk about raccoons.”

I thought of my own Dad, working these fields during the Second World War, struggling to keep the John Deere together, picking a fresh crop of rocks every spring, looking at adolescent versions of the same trees that now towered along the western horizon. If anybody had been in the safe central haven of peace in 1940, it had been him, broadcasting wheat seeds by hand, back here in The Back Field.

But the de Havilland Aircraft Co., builder of the Mosquito bomber, got some of its parts from a local factory in Orillia, Ont., and from time to time would send a bomber for a fly-past, rattling farmhouse windows and bringing a deep rumbling of patriotic pride to the workers below. It was a visceral tie to the war effort, a sudden deafening reminder that the world’s problems were a lot closer than you might think. We’re all in it together, lads – that sort of thing.

For my Dad, spreading seed in a quiet corner of Ontario in 1940, it was a jarring reality check. A reminder that no man is an island.

But that was a different time and a different war, and Sam and I enjoyed our peace, unruffled by the throaty roar of a twin-engined bomber. Somewhere off to the south we could hear a dump truck shift down for a hill, but that was it. Snow clouds were massing out over Georgian Bay but, for now, peace reigned.

Can we ever really give our children the nurturing isolation we think they need? Can we hope to preserve their innocence? We try, but are we kidding ourselves? Do the words “terrorist” and “anthrax” and “cluster-bomb” need to be part of their vocabulary?

We change the subject when the uncomfortable gets too uncomfortably close. “Let’s talk about raccoons, Sam,” I say, but I really want to say, “Sam, I wish your injured world was different, my little one.”

He asks if I’m a hero, but I think he’s really saying: “Daddy, will you keep me safe?”

Safe? How could he not be safe back here, in the quiet centre of solitude?

And then, as if cued by God for maximum effect, a massive airliner, maybe a 747, thunders by overhead, climbing from Toronto, headed for Europe. Full of people. Full of fuel. The mind’s projector wants to replay the horrible images again: the planes swinging around and lining up the towers...

Sam sees the plane too, and to him, it is right over us, its shadow ready to collide with ours. What plays on the little screen in his mind?

I want to stick out my chest like Rat in The Wind In the Willows and say, “Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World, and that’s something that doesn’t matter, either to you or me....Don’t ever refer to it again, please.”

But I can’t. It’s as clear as the vapour trail that veers sharply off to the east above us.

The Wide World is right here, Sam. And yes, little one, we are all in this together.

He takes my hand. For now, that seems good enough for him.